In the autumn of 1971, an ambitious young engineer from Talca, central Chile, strode into the lobby of the exclusive Athenaeum Club on London’s Pall Mall to meet Stafford Beer, an eccentric Surrey insider he had long admired.

Fernando Flores had been appointed head of Chile’s Production and Development Corporation (Corfo) by the socialist president Salvador Allende at just 26, and amid a rush of excitement for Allende’s plans, hoped to present Beer with his vision for a technology-driven, state-led economic model.

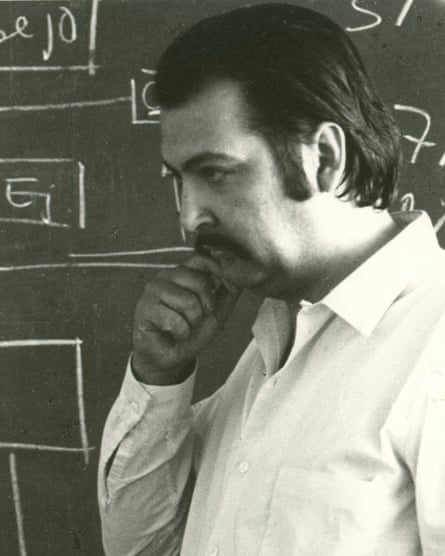

Beer was frustrated by the lack of traction his ideas were getting in Britain – he had pioneered “cybernetic management principles”, the science of effective organisation, which inspired Flores – and was quick to agree.

The meeting would blossom into a dizzying, experimental collaboration in Allende’s Chile – one of cold war Latin America’s fiercest battlegrounds – and the fruition of the Cybersyn Project, a futuristic plan for a modern socialist economy.

It was to rely on a network of telex machines to connect the factories of Corfo’s more than 80 subsidiary companies to a wood-panelled operations room in the capital, Santiago. There, seven chairs were set in a circle for Allende’s decision makers to monitor production in real time, each with a set of futuristic buttons, a cigar ashtray and space for a whisky tumbler built into the armrest.

With the 50th anniversary of Gen Augusto Pinochet’s bloody 1973 coup d’état which deposed Allende approaching this September, the tale is being highlighted in The Santiago Boys, a new, nine-part podcast series, written, researched and presented by the technology writer Evgeny Morozov.

“[In 1960s Chile,] you had a genuinely innovative agenda with regards to industrialisation and technology, and a coherent ideology which they were starting to implement,” he said.

After Pinochet’s coup, the Chicago Boys, a clique of economists educated under Milton Friedman at the University of Chicago, swiftly brought their mentor’s neoliberal ideals to Chile.

“The figure of the Chicago Boys looms large in the mainstream historiography, and they are often considered the ‘real’ innovators,” said Morozov. “But in my version of the story, it’s the ‘Santiago Boys’ who come first, and the Chicago Boys were the violent, bloody and not-so-creative response to them.”

Morozov refers to “the use of technology to pursue a political agenda: propaganda, surveillance and pursuing your enemies” as “dark tech”, andalso re-examines Latin America’s turbulent relationship with ITT, the controversial US conglomerate, at the height of the cold war.

ITT, whose Chilean holding Chiltelco Allende had nationalised on assuming the presidency, helped foment anti-Allende sentiment and funded opponents of his government in Chile in the months before the coup d’état, according to declassified cables.

The series also digs deeper into the more sinister uses of technology over the period as part of Operation Condor, the US-backed network of rightwing Latin American regimes which shared intelligence to hunt down leftist dissidents.

Operation Condor claimed the lives of as many as 60,000 people between 1975 and 1989, and some estimates put the number of its political prisoners at 400,000 more.

It was orchestrated, at least in part, from an operations centre probably situated in the Recoleta neighbourhood of Buenos Aires, and used the same telex technology as Flores and Beer’s Cybersyn Project to share intelligence.

Before Pinochet’s coup, Beer, a charismatic and sometimes volatile man who had been educated at elite private schools, drove a Rolls-Royce and even kept the company of the later disgraced media baron Robert Maxwell while living in Surrey.

After Allende was overthrown, he never returned to Chile.

He grew a beard, taught tantric yoga, wrote poetry and painted, living in Wales and Canada with few material possessions. The philosopher Humberto Maturana memorably remarked of Beer that he had arrived in Chile a businessman and left a hippy.

Beer died in 2002, and after two years researching his work and legacy, Morozov believes that his lack of formal academic training – he never completed his degree, which was interrupted by military service, or studied for a doctorate – as well as the “wrong” kind of eccentricity and his explicit links to Allende all dented his credibility in intellectual circles.

“He became more of a counterculture guy, rather than a serious thinker,” Morozov explained.

Fernando Flores was held in a prison camp in the south of Chile until his release in 1976. He moved to Silicon Valley, where he enjoyed a successful entrepreneurial career, before returning to Chile and becoming a senator.

Gen Pinochet was arrested in London in 1998 on an international warrant obtained by the Spanish lawyer Baltasar Garzón. Before his arrest, the former dictator had been staying at the Athenaeum Club on Waterloo Place where Beer and Flores first met.

Cybernetics, the field Beer was so closely related to, was largely sidelined in the 1970s by excitement surrounding artificial intelligence.

“Beer’s ideas still get discussed because he wanted information technology to be the coordinating force, not the market,” said Morozov.

“That’s why I find the legacy of the Cybersyn Project and Stafford Beer to be a very promising avenue for reinventing what socialism of the 21st century should be.”

Source : The Guardian